“It wasn’t easy for us. We grappled with lizards and other crawling animals. You could be at your desk working, and suddenly, a lizard would just fall onto your desk from the roof without warning, sending shivers down your spine. We’d then start chasing the animal around to maintain order, all the while anticipating the fall of another lizard,” Marcus Japheth, a teacher in the school, narrated.

As far back as 1991, the residents of Gawu in the Kuje Area Council of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), established a primary school to educate their children after waiting fruitlessly for the local council. Despite the absence of any existing structures, the determined community found shelter at the ECWA Church building at the heart of the community, making the commencement of learning possible. And thus, Gawu Local Education Authority (LEA) Primary School was birthed.

Three years later, the community successfully constructed a simple yet functional mud-brick three-classroom block on the designated school site, relocating their children there.

READ ALSO: Federal Government 2024 Housing Budget Falls Short of Tinubu Grand Promises

It was like that for over 18 years. Some of the pupils and teachers who had no space available for them within the classroom block conducted lessons beneath the shade of a tree. They endured until 2010 when, in response to the persistent pleas of the community, the government, through the FCT Universal Basic Education Board (UBEB), constructed an additional block of three classrooms.

This little beginning, a makeshift haven became the cradle of hope, nurturing a generation eager to learn. Markus Japheth, one of the first pupils, vividly remembers those early days.

“In the beginning, some of us learned on the floor, because it took a while before the community arranged for seats. But none of that bothered us; we were just eager to learn,” Japheth recounts.

Advertisement

School Crumbling Under Systemic Neglect

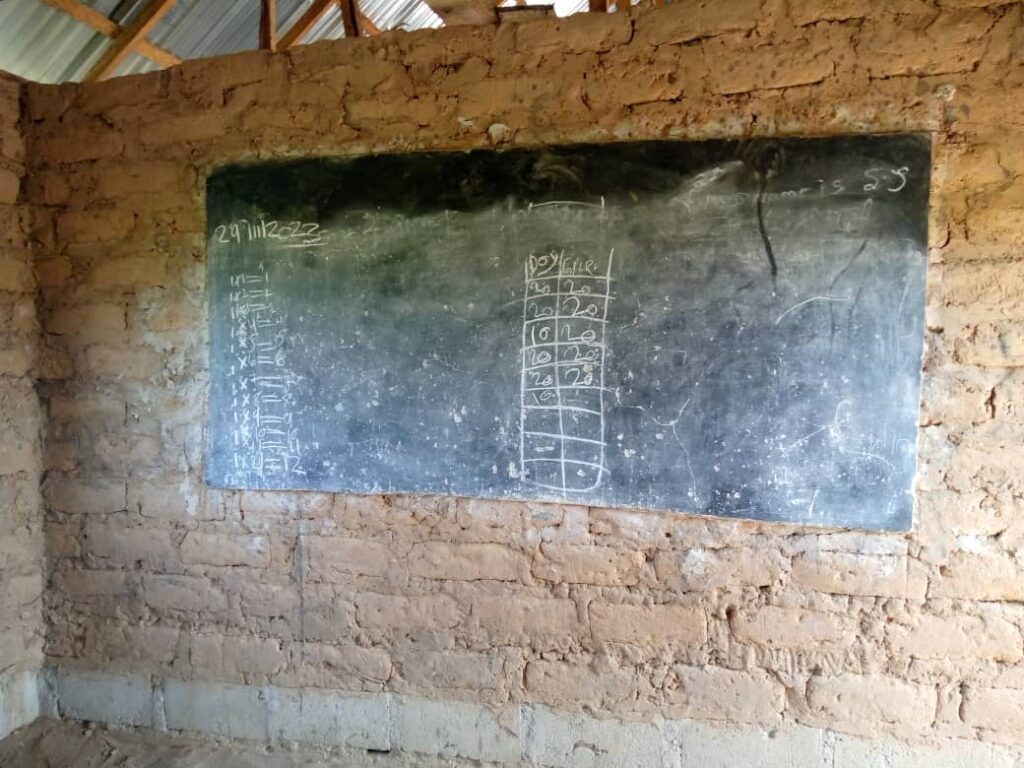

Now, the school, which gave hope of further transformation of the community, is crumbling under systemic neglect. THE WHISTLER visited the school and saw that the mud house had collapsed, with the single three-classroom block built by FCT-UBEB in 2010 standing beside it. Another mud classroom block under construction was without doors and windows. Construction was halted due to lack of funds.

Reflecting on the past and drawing connections to the present, Japheth recalled the community’s deep relief when the government stepped in to provide the classroom block in 2010.

“At that time, the children were divided between the new classroom block and the mud classrooms,” he recalled.

However, their happiness was short-lived as the mud classrooms became uninhabitable. Concerns about a potential collapse prompted the school management to relocate students who couldn’t fit into the government-built classrooms back under the tree.

“As we feared, two of the classrooms in the mud block collapsed during a rainy day. Thankfully, no one was present when it happened,” Japheth recounted.

Despite the challenges, the teachers opted not to entirely abandon the remaining part of the mud building, a single classroom. This space was repurposed as a staff room where teaching aids were stored. However, there were consequences to this.

“It wasn’t easy for us. We grappled with lizards and other crawling animals. You could be at your desk working, and suddenly, a lizard would just fall onto your desk from the roof without warning, sending shivers down your spine. We’d then start chasing the animal around to maintain order, all the while anticipating the fall of another lizard,” Japheth narrated.

Godogo To The Rescue

Advertisement

However, at the beginning of this year, the staff room also collapsed. While the community has initiated the construction of another mud classroom block, there remains uncertainty about when the school will transform into a comfortable learning environment for their children.

Japheth, who serves as both a teacher and the community’s secretary, disclosed that the residents invested over N600,000 in building the mud classrooms. The funding was primarily generated through a communal practice known as ‘Godogo,’ in his dialect, translating to community farming.

This practice involves all men in the community joining forces to farm for a member in exchange for funds saved in the community’s treasury. The farming duties rotate among community members, each contributing a predetermined amount, with the average being N12,000.

Japheth explained: “We take Godogo seriously. The Chief (traditional ruler) imposes a fine on anyone failing to participate when the farming is scheduled, and the fine is N5,000. Non-compliance with the rules might lead the Chief to involve the police, resulting in additional charges on top of the fine”

The 41-year-old father of three emphasised that the teachers, all native to the community, individually contributed N30,000 from their salaries to support the project. This contribution, however, was spread over a period rather than a lump sum.

Unfortunately, the construction has come to a halt due to insufficient funds, leaving the classrooms in an unfit state for learning.

“The building has been erected, but we lack the funds to floor it, resulting in dusty floors. The walls are yet to be cemented, and we’ve only managed to buy cement for the construction of chalkboards. There are no windows, and the seats are broken,” Japheth explained.

Challenges In School

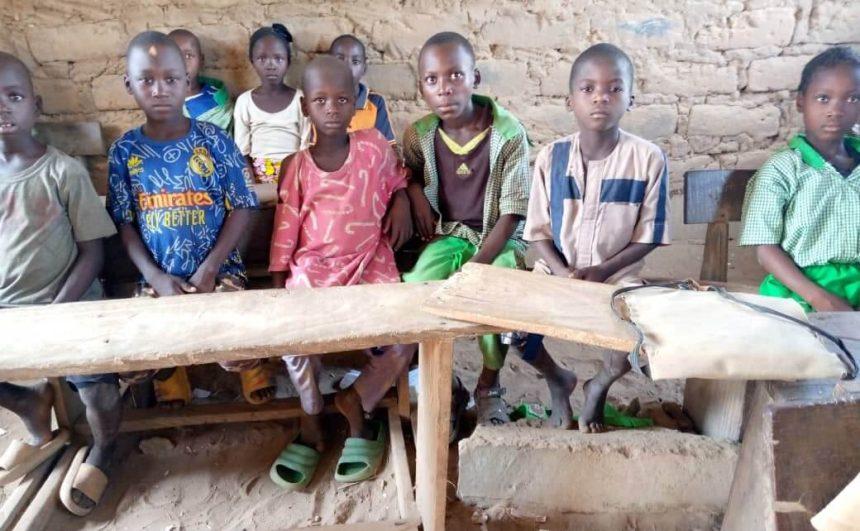

With a student population of 206, even with the addition of the incomplete mud building, the classrooms remain insufficient. A temporary shade behind the government-built block now serves as a classroom for Early Childhood Care Development and Education (ECCDE) pupils.

“The temporary shade was initially used as a storeroom during the Home Grown Feeding Programme (HGFP), which was later suspended. Now, we use it to accommodate Nursery 1 and 2 pupils. One of the classrooms in the government-built block serves as our staffroom, while the other two are for primary 5 and 6 pupils. The mud structure caters to the Primary 3 and 4 pupils,” Japheth clarified.

“The building is not conducive. We lack proper sitting arrangements. In the makeshift shade, children sit on the ground. One seat accommodates four or five pupils, leaving them with minimal space,” he elaborated.

Japheth highlighted that the inadequate infrastructure and shortage of seats have significantly impacted the students’ learning experience. “During lessons, the children easily distract each other due to the close seating arrangement. The teacher often has to pause teaching to restore calm before continuing. This leads to a considerable amount of time being wasted that could have been utilized for teaching,” he explained.

Furthermore, the school grapples with a lack of teachers and teaching materials. Currently, it has four male teachers, one female staff member serving as a clerk, and a male volunteer teacher who was formerly a student at the school.

“I handle two classes, teaching Primary 3 and 5. The other teachers manage the remaining classes. I devised a timetable to manage the teaching workload. It’s challenging, but we are doing our best to provide the children with a quality education,” Japheth remarked.

Ex-Student Returns

Solomon Gushara, a former student who graduated in 2012, shared a tale of disappointment as he witnessed the enduring challenges of his alma mater 11 years later. He has now received a National Certificate in Education (NCE). He found it disheartening that the issues he faced as a student still persisted.

Recalling the hardships during his time, Gushara, who served as an assistant head boy, said: “We faced a lot of challenges. The heat made us uncomfortable, and there weren’t enough seats. Many students had to sit on the floor.”

Motivated by a deep sense of community belonging, Gushara, now 22, volunteered to teach in the school, driven by a desire to alleviate the struggles faced by the teachers. He emphasised the significance of quality basic education and expressed his wish for an improved educational environment at his alma mater, envisioning a brighter future for the current students.

Reflecting on his own journey, he revealed: “The challenges in this school, which I experienced, affected the way I related with my peers during my tertiary education days, but I was still able to catch up, by God’s grace.”

Gushara expressed sorrow over the apparent decline of the school, noting that instead of progressing, it has regrettably continued to depreciate in standard.

An Appeal For Assistance From The Government Met With Silence, The Blame Game Continues

The residents of the community have expressed their frustration, stating that they have written multiple letters to the FCT Universal Basic Education Board (FCT-UBEB) through the area council but have received no responses.

The Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) is a federal government agency responsible for coordinating all aspects of the universal basic education (UBE) program implementation. Meanwhile, the FCT-UBEB was established to manage early child learning centers, primary schools, nomadic schools, special needs schools, and junior secondary schools in the FCT.

As the communities blame the FCT and UBEB for the lack of response, the board cites limited resources and community initiatives as significant challenges. Unfortunately, the ultimate victims in this ongoing struggle are the children, who are being denied their fundamental right to a quality education.

Pupils at a zinc classroom at Gawu Local Education Authority (LEA) Primary School

FCT-UBEB Responds

THE WHISTLER contacted Dr. Hassan Sule, the FCT UBEB chair, regarding its findings. He attributed overstretched facilities in the capital territory to insecurity and population influx. Sule acknowledged challenges in the education sector but rather emphasised that education is a collective responsibility for all Nigerians.

He acknowledged the existence of community-initiated schools in the FCT, starting independently before seeking board approval. He assured ongoing efforts to integrate these schools into the system and address their needs.

Explaining the process, Sule stated: “They usually contact us through the LEA and Area Councils, and we will come and check if they have the needed facilities like classrooms and land. We will then approve, and the government will intervene and support them according to their needs.”

He showed documents indicating the board’s acknowledgment of challenges and a pledge to address schools’ requirements. Notably, Gawu LEA School in Kuje Area Council was identified for the provision of blocks of classrooms. Sule said he has established a committee to inspect schools across the FCT by January, aiming to implement an action plan.

Sule, however, failed to provide clarity on whether LEA Gawu, which has existed for over 32 years, hasn’t been integrated into the system yet.

This report is produced by Safer-Media Initiative under The Collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusivity and Accountability Project (C-MEDIA Project) of the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.

Source: The whistler