The Nigerian government has cut electricity exports to Niger Republic by nearly half, dropping its supply from 80 megawatts to just 46MW — a move that’s deepened the energy crisis in the junta-led nation.

The development was confirmed by Niger’s Energy Minister, Haoua Amadou, in an interview with AFP, amid growing complaints from citizens over prolonged blackouts and a growing shift toward solar alternatives in the country.

The impact has been significant. With output now falling between 30 to 50 percent, Niger’s national electricity firm, Nigelec, has resorted to rotating power cuts — some of which last for days — especially in the capital city, Niamey.

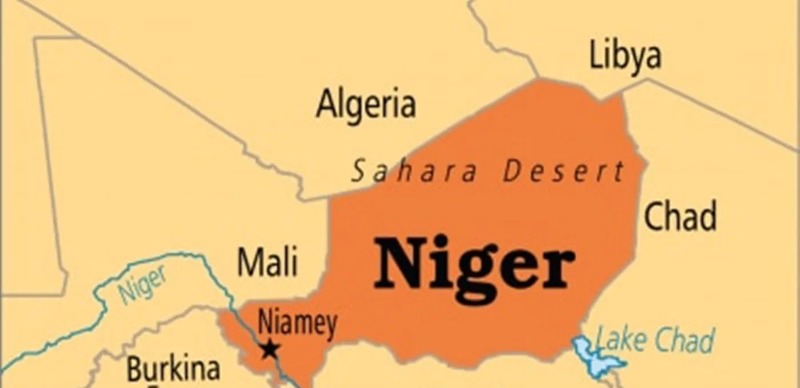

Electricity exports to Niger were initially suspended by Nigeria in July 2023 following the ousting of democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum by members of the Presidential Guard. In response, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposed sweeping sanctions, including halting all energy transactions.

While the suspension was eventually lifted, electricity supply from Nigeria has remained restricted — and, according to Amadou, far below what’s needed to meet Niger’s growing domestic demand.

“Nigeria has resumed deliveries, but we’re only receiving 46 megawatts, well short of the previous 80MW,” the minister said.

The shortages have fueled a surge in solar power adoption across the country. In neighborhoods like Lazaret in Niamey, residents have taken matters into their own hands.

“Power cuts are no longer a problem for us. We’ve gone fully solar, and there are no bills to worry about,” said local resident Elhadj Abdou, pointing to the solar panels lining rooftops in his area.

These Chinese-imported panels, which cost around 50,000 CFA francs (about 75 euros), are now a common sight on the streets, sold directly to households and small businesses.

Nigeria, for its part, primarily relies on natural gas and hydroelectric sources to generate electricity, with over two dozen thermal plants supplying the bulk of its national grid.

Despite the partial resumption of supply, observers say the reduced electricity allocation reflects lingering diplomatic unease following last year’s coup — and the broader political uncertainty surrounding the region’s energy diplomacy.