The last week of January was “a week of panic” for employees of the YWCA of NorthEastern New York. With no warning, they were locked out of a federal payment system that allows the Y to provide services for people experiencing domestic violence, teen and youth programs, housing assistance, and more.

The lockout was a result of an Office of Management and Budget (OMB) memo instructing federal agencies to freeze payments until they showed they were in compliance with a series of executive orders Donald Trump issued shortly after he was inaugurated.

“There was no day to prepare,” says Tamara Flanders, the organization’s housing director. “We were not able to access that money for 48 hours and had no idea if we would be able to access it.”

That scene played out across the country for a little more than a day, until a federal judge blocked the freeze on Jan. 28 and OMB rescinded its memo the next day. While the immediate crisis has lifted for Flanders’ organization and others (but not all), the fear that the federal government may again renege on its contracts still hangs over many federal grantees.

Shelterforce spoke with a dozen different federal grantees—including organizations that provide rental assistance, affordable housing developers, groups that fight discrimination in housing, and housing researchers—as well as membership associations and advocates that represent many more such groups, about how the situation is affecting them now and how it could affect them in the future.

The primary executive orders that might affect grantees across the housing and community development world are:

- Number 14151, which calls for the withdrawal of federal funding from any program associated with diversity, equity, inclusion (DEI); accessibility, or environmental justice.

- Number 14168, which denies the existence of intersex and transgender people. (On Feb. 7, newly confirmed HUD Secretary Scott Turner followed this up by saying he would stop enforcement of a 2016 rule that ensures housing and shelter providers serve clients on the basis of their gender identity.)

- Number 14154, which calls for a pause in disbursing grants under the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

The legality of these executive orders and how they will be implemented is unclear. On Friday, Feb 21, right after this article was first published, a judge issued a preliminary injunction against the anti-DEI order, saying it violated the first amendment, According to the order, federal agencies would have had to report back to the administration about their grantees’ compliance with the anti-diversity, equity, and inclusion orders by Thursday, March 20. Ongoing legal challenges are expected.

Niyati Shah, director of litigation at Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC, which is representing plaintiffs in one of those legal challenges, calls the executive orders “purposefully incendiary.” “In signing these orders,” Shah wrote in an email, “the President is seeking to unlawfully suppress ideas that he personally disagrees with and threatening them with potentially disastrous monetary and legal consequences.”

Philip Tegeler, executive director at the Poverty and Race Research Action Council, a civil rights law and policy organization, agrees. “Many of the executive orders are unlawful,” Tegeler says. For one, he says the president doesn’t have the authority to withhold funds that have already been dedicated by Congress. “We’re going to have to rely more and more on the courts,” Tegeler says.

But the legal path will probably involve the executive orders—and the funding they affect—being “paused and unpaused” over and over again, until they are eventually brought to the Supreme Court for a decision, notes Thomas Silverstein, director of the Fair Housing and Community Development Project for Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “I don’t think anyone knows what’s going to happen here.”

And, of course, in the background of these fights over already appropriated funds is the specter of draconian budget cuts for upcoming years making their way through Congress this spring.

Effects Could Be Dramatic

The executive orders will no doubt affect the funding of a wide range of housing programs in the U.S., but it’s unclear just how extensive or aggressive those cuts will be. Even though “rental assistance” was nominally exempt from the January funding freeze, there is still a danger that people relying on federal programs for their housing might lose that support, and eventually their homes.

The YWCA of NorthEastern New York, for example, houses about 110 people, including 70 families, through two programs that are funded exclusively by HUD. They provide trans-inclusive housing, and the organization has a specific mission to fight racism, two things that could put the Y’s funding in the executive orders’ crosshairs. “Not all of our tenants follow the news,” says Flanders, “but for those who do, the thought of an eviction and losing their housing was extremely panic inducing for them, and for us.”

What We’re Reporting on Next

Patricia Kidd, executive director of the Fair Housing Resource Center Inc., in Painesville, Ohio, told the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) that 98 percent of the organization’s funds come from HUD. This includes a HOME grant that provides rental subsidies for 21 households composed of seniors and persons with disabilities. “Without access to the funds, these households are at risk of becoming homeless,” she reported.

Nonprofit housing developers are also concerned that projects that serve specific populations might be in jeopardy. The executive orders call for the defunding of programs that are associated with “accessibility.” This could affect organizations like The Kelsey, a nonprofit developer of affordable, accessible housing. To fund its projects, The Kelsey uses HUD’s Section 811 funding, which specifically targets housing for disabled residents. Caroline Bas, the organization’s chief operating officer, says there’s “no certainty that those projects are going to be able to continue in their current form . . . We are assuming that the projects that rely on those programs are not going to be feasible or [will be] greatly delayed while we pull together other funding sources.”

Other organizations are worried about unreliable funding in general.

LeadingAge represents nonprofit organizations that serve older adults, including affordable housing organizations. Due to the funding freeze, some members still haven’t gotten funds that were obligated to them by HUD, leading to concerns that the money they need to operate will be unreliable in the future.

Linda Couch, LeadingAge’s senior vice president of policy and advocacy, can think of several potential consequences, which “start with staff layoffs, and probably putting off big capital repairs, and maybe putting off regular maintenance and then maybe not turning over units because you don’t have the resources to paint or to flip a unit to the next available tenant. And then you just see waiting lists get longer. And then before you know it . . . you might just not have enough money to pay your electric bill.”

Fair housing organizations may also be targeted. The first Trump administration was marked by an active distaste for fair housing enforcement, which addresses discrimination against buyers and tenants based on their being members of protected classes such as race, nationality, sex, gender, family status, and ability.

Lila E. Hackett, executive director of the Fair Housing Center of Northern Alabama, told NFHA that her organization mostly helps disabled people, older adults, and veterans with discrimination complaints, but that “due to the lack of local funding for fair housing in our 29 counties service area, the withdrawal of federal support would completely curtail our services.”

Federal funding often ensures that services local governments can’t or won’t fund still reach all parts of the country.

The loss of federal funding could hit organizations working on racial equity and opportunity in right-leaning areas hard. Enterprising Latinas, which helps women in Florida’s Tampa Bay area start businesses and achieve economic mobility, had already faced pushback from Republican officials before Trump took office. In 2023, grant funding for one of the organization’s projects was pulled after newly elected Republican officials took office.

Elizabeth Gutierrez, the organization’s founder and CEO, says she’s been preparing to apply for direct federal funding to start a CDFI since she’s quite sure her organization will no longer be considered for local funding. “Our hope really fell in the hands of the federal government,” she says. “It’s devastating to consider that we may not survive.”

Research on housing, disaster relief, and more could also be stalled. HUD’s Hispanic Serving Institutions and HBCU Centers of Excellence were included in the round of stop work orders that went out following the OMB memo, though all of their funding had already been disbursed, raising the prospect that the administration may also try to claw back funds already awarded. If that were to happen, research projects from a study of housing insecurity among aging North Carolinians to a look at possibilities for expanding housing supply in Phoenix, Arizona, could grind to a halt, and graduate student researchers could abruptly lose their jobs.

Looking even longer term, there are many potential ripple effects of the federal government deciding that it does not have to honor its contracts or Congress’s appropriations.

“When federal funding becomes unpredictable, it doesn’t just affect government-supported projects—it also chills private investment in low-income communities,” points out Frank Woodruff, executive director of the Community Opportunity Alliance, in a written statement. “Developers, lenders, and philanthropic partners rely on federal dollars as foundational capital that reduces risk and attracts additional funding. When that foundation is unstable, the entire investment ecosystem hesitates.”

Unclear How to Respond

Though there is so much at stake, there’s frustratingly little for potentially affected organizations to do now except wait and try to plan how they will respond if their federal funding agency withdraws their funds, or asks them to drop a particular part of their work.

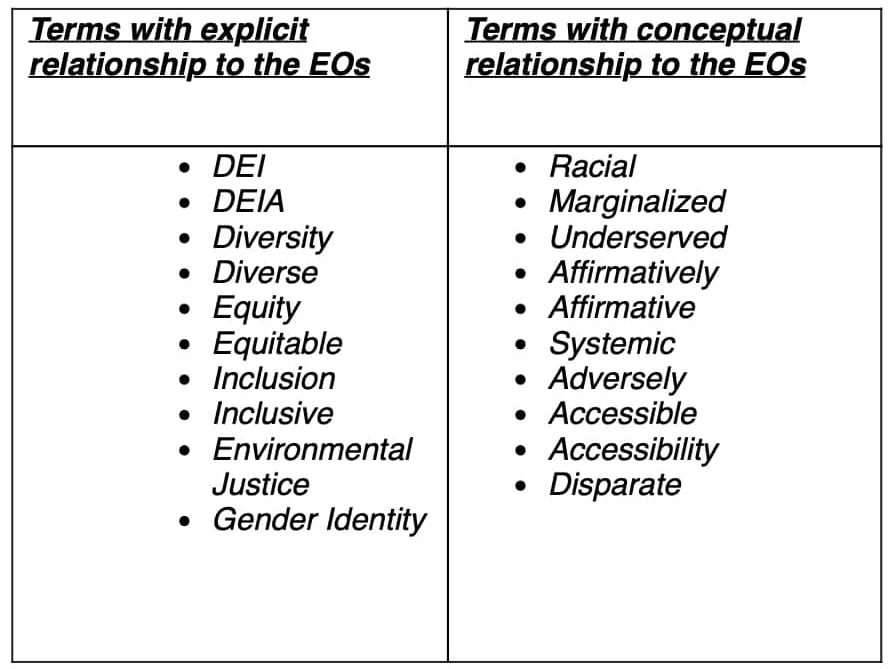

None of the organizations Shelterforce spoke with had yet received any direct guidance about whether their contracts would be affected, so they are left trying to guess. Though one HUD office shared a list of words they will be looking for when assessing whether a program adheres to the president’s executive orders, it is unclear if the watch words will be consistent throughout or across agencies, and how much discernment officials will apply when they find them.

“There’s so much trickery in the wording,” says Flanders. “What do you mean by DEI programming? We’re not using the money to pay for [DEI] trainings, but our mission statement is ‘empowering women and eliminating racism’. . . We provide trans-inclusive housing. The money doesn’t go towards gender affirming surgery, but it goes towards gender-affirming, safe housing. . . . So would we make the cut? We don’t know.”

The director of one statewide housing organization that receives both federal and nonfederal funding noted that she didn’t know what was coming, but was preparing for a conversation with her board about exactly where their “line in the sand” would be.

Silverstein agrees that the DEI executive order is too vague to interpret reliably. “How do you know what you are supposed to be doing to not be in hot water later?” he notes. And, for example, he asks, is accessibility targeted because it shows up sometimes in a list with diversity, equity, and inclusion, or do they really not want anyone to investigate whether a developer has violated the Fair Housing Act and Americans with Disabilities Act?

“There’s no definition of what DEI means in anything,” says Shamus Roller, director of the National Housing Law Project, “so what’s happening across the federal government is that they’re just eliminating, you know, anything that says anything about anybody who’s not like a white dude. It’s just a bizarre dynamic.”

Deirdre Pfeiffer is an associate professor at the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University and principal investigator of the Arizona Research Center for Housing Equity and Sustainability (ARCHES), a HUD HSI Center of Excellence. ARCHES is working on 20 different research projects covering a wide range of housing topics important to people in the state of Arizona. Many would even align with some of the priorities of the current administration, she says, such as ways to increase housing supply, or identifying regulatory barriers facing homeowners or property owners. And yet, she notes, “equity” is in the name of the center and so “our concern is that there might be . . . a hammer approach, rather than a surgical approach” to implementation, with people making “assumptions about who we are and what we’re doing based on titles or names of funding programs or maybe even the name of our center alone, without looking into who we are.”

Shah, of Asian Americans Advancing Justice – AAJC, thinks this vagueness points to likelihood of arbitrary enforcement. “What ‘DEI’ and ‘DEIA’ means to this administration and this President is ever evolving based on whomever is next on their target list,” she wrote.

Faced with this level of uncertainty, many groups are just hoping to avoid being caught in the dragnet, while actively planning for the worst. Jeremey Newberg, CEO of Capital Access, which has 25 different HUD technical assistance assignments and has been a HUD technical assistance provider since 2000, says the temporary payment interruption was challenging, but “also a constructive exercise in crisis management and resilience.” They are back at work on all of their contracts, but he is struggling a bit to keep his staff from succumbing to “alarming algorithms.” Nonetheless, “we are a transparent shop and welcome new leadership to inspect our service delivery,” he wrote in an email.

We provide trans-inclusive housing. The money doesn’t go towards gender affirming surgery, but it goes towards gender-affirming, safe housing. . . . So would we make the cut? We don’t know.”

Tamara Flanders, YWCA of NorthEastern New York

“Right now, we’re sitting tight and just looking at the other grants that we’ve gotten from foundations and financial institutions, and some nonfederal dollars as backup,” says Sandy Deters, housing counseling coordinator at Embarras River Basin Agency in Greenup, Illinois.

The swath that is cut could be wide. During the Biden administration’s time in office, says Tegeler of the Poverty and Race Research Action Council, an emphasis was placed on equity and inclusion, so “it’s going to be difficult to find a grant proposal in response to a Biden administration NOFA [notice of funding availability] that doesn’t have some forbidden phrases in it.”

Fair housing advocates, while they do not hope to fly under the radar, are relying on the fact that they are engaged in enforcing the federal Fair Housing Act. “An executive order cannot override a federal statute,” says Nikitra Bailey, executive vice president of the NFHA, “so we would take the position that any action to do that would be unlawful.”

Thomas Okuda Fitzpatrick, executive director of Housing Opportunities Made Equal of Virginia (HOME), a fair housing nonprofit, says they have “reviewed the administration’s stances on diversity, equity and inclusion,” but don’t think they are affected, because “what we’re working on is anti-discrimination, and that’s rooted in the law.”

Neither ICF nor HUD returned requests for comment.

There may be more decisions coming for some organizations. Technical assistance providers working under HUD’s Community Compass program were notified in a Jan. 24 email from HUD that if their work was found to be not aligned with the executive orders, they should submit their final billing and close themselves out of the system. That email also addressed existing HUD resources, stating that the lead Community Compass grantee, a large consulting firm called ICF, has been tasked with combing through all the printed material on the HUD Exchange resources page for various words related to the executive orders, and archiving or requesting revisions from grantees of anything determined to not comply with them. Grantees who have equity-related publications on HUD Exchange will need to decide how to handle revision requests. (None reported receiving any yet.)

Staying the Course

Many organizations are vocally staying true to their mission. “I want to be clear: the Alliance remains committed to equal access,” wrote Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness in a statement. Oliva stressed that the rule to recognize gender identity in offering shelter is still legally in place even though HUD has said it won’t enforce it—and so are the rights of trans and nonbinary people who need a place to sleep. “The Alliance strongly urges system leaders and providers to have policies in place to ensure that everyone has access to the life-saving shelter and services that they need, regardless of HUD’s decision.”

Gutierrez of Enterprising Latinas is moving forward with her CDFI application, but she won’t be trying to change anything about how she described her organization in the process.

“There is no way, for the benefit of money, or staying out of people’s crosshairs, that we will change who we are,” she says. “These are initiatives that make it possible for people to no longer be living off the system, which is what Republicans want. They want people earning a check for themselves.”

Shannon Van Zandt is a professor at Texas A&M University’s School of Architecture and interim director at its Center for Housing and Urban Development, another HUD HSI Center of Excellence. “My entire research agenda is focused on social vulnerability to disasters,” she says. “And that itself might be considered DEI because I’m pointing out the disparities in how people are treated by policies and programs due to something that is beyond their control.” Though she has received federal research grants from many agencies, she is skeptical about whether that will continue. But she is clear about her own path forward if that happens: “If I can’t get funding for my research, then I’ll just continue to write and speak about what I know is true and what is happening out there, and work with the data sources that I can, and talk to the people that I can,” she says. “I’m not going to stop.”

Flanders says that the YWCA USA did have some emergency meetings with its chapters and entertained going quiet and dialing back the equity language in their mission. But for now, the conclusion was, she reports, “We’re not hiding who we are. We’re going to continue to provide the care that we do to the population that we serve. We’re not changing our mission statement. . . . We’re just going to have to see where the cards fall.”

“There’s a lot of energy, and rightfully so, concerned about what’s happening at the national level,” says Fitzpatrick. “But the reality is, so many decisions that impact the communities we serve are really done at the local and state level . . . and so where folks need to drive their energy, if they’re really concerned about their neighbors and their friends, is to get involved at the local and state level and support organizations like HOME that are making sure that the landscape here is welcoming and inclusive.”

“People say to me ‘are you afraid?’” says Gutierrez. “And I can tell you fear is not the thing that I feel. I have many feelings, fear is not one of them.”