BY: Oluwole Crowther

An industrial giant like China is highly strategic when it comes to macroeconomic decisions. China doesn’t follow trends or implement policies without assessing their long-term benefits. Its economic policies are carefully crafted to ensure that they align with national goals and strengthen its competitive edge in global markets.

“While theory suggests that trade balance will improve after a devaluation, this improvement relies on a country’s capacity to produce and export efficiently.”

BY: Oluwole CrowtherAn industrial giant like China is highly strategic when it comes to macroeconomic decisions. China doesn’t follow trends or implement policies without assessing their long-term benefits. Its economic policies are carefully crafted to ensure that they align with national goals and strengthen its competitive edge in global markets.

One such decision was China’s devaluation of the yuan in 2019, which sparked global debate and raised questions about currency devaluation as an economic tool for developing countries like Nigeria.

China: The “currency manipulator” debate

In August 2019, the U.S. Treasury labeled China a “currency manipulator” after the yuan’s value was weakened amidst escalating trade tensions. Donald Trump, U.S. President at the time accused Beijing of devaluing its currency to gain an “unfair competitive advantage” by making Chinese goods cheaper in international markets.

According to data from the World Bank, the Chinese yuan depreciated by 4% in 2019, and the U.S. Treasury claimed this move was a deliberate attempt to preempt the new tariffs imposed by the U.S. that were set to take effect in September of the same year.

Despite the devaluation and the tariffs, China’s overall export value grew by 2.62 percent on average between August and December 2019. However, its exports to the U.S. declined by an average of 2 percent during the same period. This illustrates how a country like China can leverage devaluation as part of a broader economic strategy to cushion the effects of external pressures.

Nigeria’s currency devaluation: A similar move with different results

In June 2023, Nigeria devalued the naira by 51 percent, following recommendations from international financial institutions and other finance experts. However, it appears that the nation is not taking advantage that comes with devaluation when one compares it to how other countries have benefitted immensely from it.

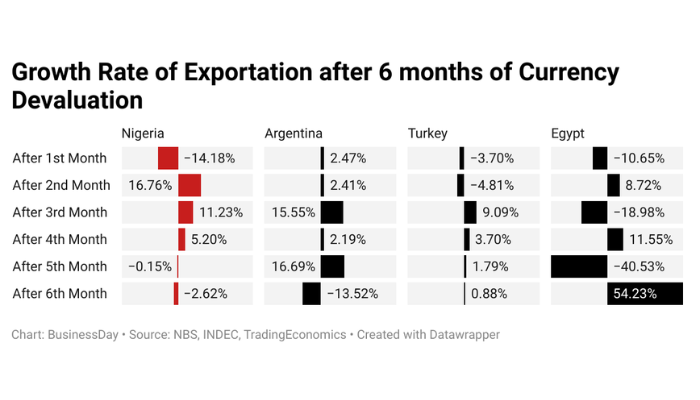

According to BusinessDay analysis, Nigeria’s export growth rate averaged 1.88 percent in the months (July 2023-June 2024) following the devaluation. When compared to the scale of the devaluation, this modest export growth suggests that devaluation, in isolation, may not significantly improve the nation’s exports.

While China’s devaluation was a strategic response to global trade dynamics, Nigeria’s currency devaluation aimed to attract foreign capital and enhance the country’s investment appeal. However, unlike China’s carefully managed approach, Nigeria’s economic environment lacked the structural reforms necessary to fully capitalise on such a move.

The J-Curve effect: Why evaluation Isn’t Enough

One of the key theories related to currency devaluation is the J-curve effect. This theory suggests that after a devaluation, a country’s trade balance may initially deteriorate before improving as exports become more competitive.

By extension, Nigeria’s exports grew by 2.71 percent on average between January and June 2024, a sign of a partial response to the J-curve effect. However, this growth is modest, with average exports totaling $4.9 billion in twelve months. In comparison, China achieved over $221 billion in just five months post-devaluation, while Turkey managed $21.9 billion in seven months after a similar move.

Nigeria’s limited response to the J-curve is largely due to structural weaknesses in its economy. While theory suggests that trade balance will improve after a devaluation, this improvement relies on a country’s capacity to produce and export efficiently. Nigeria’s infrastructure, industrial capacity and ease of doing business remain significant barriers to fully realizing the benefits of devaluation.

Currency devaluation should be a powerful tool for any government with solid economic and political foundations. However, in Nigeria’s case, this has not been the reality.

The Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN) reported that 767 manufacturers shut down and 335 became distressed in 2023 due to exchange rate volatility, inflation, and other economic challenges.

A weaker currency further strains manufacturers and businesses already dealing with an unfriendly economic climate, limiting the advantages that a devalued currency could provide.

To date, Nigeria has yet to fully capitalize on the benefits of currency devaluation due to these entrenched economic issues.

The Vietnam example: Growth before investors

While Nigeria continues to seek foreign investors through currency devaluation, and global tours, a critical question remains: What is Nigeria offering? Investors are attracted to economies that demonstrate sustainable growth and opportunity.

Vietnam serves as a prime example. Despite being left behind by the U.S. after years of war which ended in 1975, experienced heavy currency depreciation that averaged over 330 percent between 1987 and 1991, yet, Vietnam transformed itself into a global manufacturing hub.

Its economic reforms and strategic growth have attracted major foreign investors, including tech giants like Samsung.

In September 2023, U.S. President Joe Biden made a high-profile visit to Vietnam, a significant moment that underlined the growing economic and geopolitical importance of the Southeast Asian nation. Biden’s visit wasn’t just a diplomatic gesture, it was a recognition of Vietnam’s economic prowess.

In 2022, Vietnam became the second-largest exporter of smartphones, with exports to the U.S. exceeding $108 billion. This economic growth, driven by manufacturing and technological exports, is what drew the attention of the United States.

The lesson for Nigeria is clear: Investors follow growth. For years, Nigeria has embarked on global tours and currency devaluation to attract foreign investment, but without significant improvements to its economic fundamentals such as infrastructure, security, and governance, foreign investors remain hesitant.

Vietnam’s economic success shows that sustained reforms and a favorable business environment are far more attractive to global investors than short-term policies like currency devaluation without industrial capacity to maximise its benefit.

The challenges of currency devaluation for Nigeria

Devaluation can only be effective when other economic fundamentals are in place. While it may temporarily boost exports by making goods cheaper for foreign buyers, devaluation often increases the cost of imports, which is a major issue for Nigeria, a country heavily reliant on imported goods and services.

For Nigeria to truly benefit from any currency devaluation, it must address several critical issues:

High cost of doing business: Without improved infrastructure, access to energy, and reduced bureaucratic hurdles, businesses will continue to struggle regardless of currency adjustments.

Inflation: Devaluation often fuels inflation, as the cost of imported goods rises. This places additional burdens on consumers and businesses alike.

Export diversification: Nigeria’s economy is overly dependent on oil exports, making it vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. The country must diversify its export base to gain long-term benefits from any devaluation.

Moving beyond devaluation: The path forward

For currency devaluation to yield meaningful results, it must be part of a broader economic reform agenda. China’s devaluation strategy worked because it was implemented alongside strong industrial policies, infrastructure development, and a focus on long-term economic growth.

In contrast, Nigeria’s devaluation was primarily a response to short-term fiscal pressures and has so far failed to generate substantial export growth or economic recovery.

Vietnam’s success further demonstrates the importance of building a strong economic foundation before seeking external investment. Foreign investors are not attracted to economies that rely on devaluation to mask structural weaknesses. Instead, they seek markets with stable growth, diversified exports, and a favorable business climate.

Conclusion: Devaluation is not a cure-all

Nigeria’s decision to devalue the naira in 2023 has not brought the desired economic growth, and it underscores the need for a more comprehensive approach to economic management. Devaluation may provide short-term relief, but without addressing the underlying issues of infrastructure, manufacturing capacity, and governance, it cannot serve as a long-term solution.

Investors follow growth, not necessarily currency adjustments. For Nigeria to attract sustainable foreign investment and grow its export base, it must invest in economic reforms that create an enabling environment for businesses to thrive.

The experiences of China and Vietnam show that devaluation can work, but only when it is part of a larger strategy aimed at long-term economic development.